This month’s Industry Insider interview is with a name you likely know well–author, librarian, blogger, podcaster, and reviewer Betsy Bird. Welcome, Betsy!

This month’s Industry Insider interview is with a name you likely know well–author, librarian, blogger, podcaster, and reviewer Betsy Bird. Welcome, Betsy!

She’s the Collection Development Manager of Evanston Public Library, and the former Youth Materials Specialist of New York Public Library. She blogs frequently at the School Library Journal site A Fuse #8 Production, and reviews for Kirkus and The New York Times on occasion.

Betsy also hosts two podcasts, Story Seeds, which pairs kids and authors together to write stories, and the very funny Fuse 8 n’ Kate where she and her sister debate the relative merits of classic picture books. Plus, she’s a terrific writer who’s edited anthologies, written middle grade novels, and authored picture books like Giant Dance Party and The Great Santa Stakeout.

Let’s move on to the interview to find out what, why, and how Betsy manages to do all these amazing things!

RVC: How do you think about yourself in terms of your professional identity? Are you a librarian who writes and podcasts and more? Are you like a writer who also librarians? How do you keep it all straight?

BB: Man, I tell you, when I was starting out, I wanted to be like THE EVERYTHING of children’s literature. I wanted the academic side and I wanted the writing side and I wanted the librarianship side. And I didn’t want the teaching side. So, forget about that. But I wanted all the different parts of the personality of a children’s literature person that you could possibly cram into one human. At this point, it hasn’t gotten any less confusing. And I’ve certainly written more books. So, now it mostly just falls between librarian and author, but there’s the podcasting. And then the blogger part is a distinct part. So, I guess anything else falls into the blogger sphere. Podcasting…that’s a blog thing, right? So, that sort of falls into that area. And if I write an article for something…yeah, I’m not sure what I am. I’m a mess!

RVC: From one mess to another, I understand completely.

BB: Excellent.

RVC: Let’s jump back to the beginning here. What was that first picture book love moment where it all just clicked?

BB: The thing is, there’s not a click moment if it’s just what you breathe. There’s not a moment where you suddenly wake up one day and you’re like, “Air is amazing!” Because you’ve always had it.

RVC: So, you had a childhood with lots of books.

BB: I grew up in a house with books, yes–there were picture books everywhere. It wasn’t like it was even given as an option. It was just this thing one does. So, I had my books, and I had books that I really liked.

The idea of becoming an author probably didn’t come until I realized I had an aunt who was an author. That made it seem like a legitimate job that people have. I was like, “Okay, so that’s a thing.” But yeah, there was no click, there was no lightning flash to love books.

RVC: Did you have any favorites though, either authors or books?

BB: Absolutely. Yet when people ask you that, you’re supposed to say something cool. Like “Shel Silverstein was a god to me.” I mean, I like Shel Silverstein, but who I loved was very uncool. Very, very uncool. When I say her name, people who know her are like, “Oh, that isn’t cool. You’re right.”

RVC: I SO have to know now. Please dish.

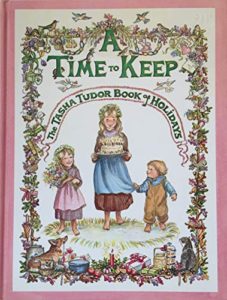

BB: Tasha Tudor. Totally not cool, since it looked like the 1880s. But she didn’t live then–she wrote a lot in the 1950s and 60s, but she dressed like she lived a century prior.

She had this book, A Time to Keep, and it was my Favorite Picture Book of All Time. I read that thing to death. I’ve still got it in my home. My children refuse to look at it, but that’s okay because it’s my book. Mine!

She had this book, A Time to Keep, and it was my Favorite Picture Book of All Time. I read that thing to death. I’ve still got it in my home. My children refuse to look at it, but that’s okay because it’s my book. Mine!

RVC: I feel your pain because my honest answer is The Saggy Baggy Elephant. Why did I like it? Because he was saggy. Nothing more, nothing less.

BB: Oh, yeah. You DO feel my pain!

RVC: Exactly!

BB: Tasha Tudor knew how to draw cupcakes REALLY well. That’s it. That’s all a kid needs.

RVC: When did you really start to think about the kidlit world as a career pathway for you?

BB: I always assumed I’d be a librarian. So, that was just considered the thing that I would do. Growing up, when we got VHS tapes, I was the kid who made an entire cataloguing system–they had all those little numbers on the side of them, remember? I alphabetized the family’s books. With our National Geographic magazines, I’d make subject heading lists to go with them. Just in case I needed capuchin monkeys for a report…which I never did.

In college, I thought it’d be cool to be a photographer. Though I’m a terrible photographer, which I know because I have just enough talent to recognize who is a good photographer. So, I did go to library school with the idea that I’d be an archivist. I wanted to preserve books. I was going to be THAT person.

Yet I took a kids book class on a lark. Now, I was already reading kids books, and had been reading then for years. When I went on my foreign study program, the second Harry Potter book had just come out. My mom told me to buy it, because somehow She Knew. And I read the entire thing that first night. And I’ve been reading like Philip Pullman and more. So, I took that kid literature course and saw that it was books I’d been reading already on my own, which hit me like a little lightning flash. It was like, “Boom, this is what I do!”

RVC: Now, you’re the first official librarian I’ve ever interviewed at OPB, and I’ve been saving this librarian question. Now it’s time to unleash it. Here goes.

Did you ever have one of those amazing moments where you you recommended a book, and a kid came back after having read it, and their life had been changed?

BB: Apparently I did and didn’t know it at the time. Just a week or two ago. Stephen Savage–a picture book, author/illustrator–sends me an email. He says, “I was in New York, and I was in a restaurant…”

Now, for this story to work, you have to understand that I skim email, so…

Steve wrote, “I saw Fred Hechinger. And he saw my New York Public Library mask and he asked if I knew you, and he said, ‘Betsy Bird changed my life.’ ” And I’m sitting there going…who the HECK is Fred…wait…there was this kid named Fred from three different book groups a while back, and though he was like 10 then, he’d go to YA panels to discuss things, and he was just a delightful, charming kid. You know, I think he like interned at Scholastic for a while.

I was like, “Fred, good old Fred!” But I have no idea how I changed his life. Did I give him a reference? No idea. Did I give him a book he really liked? Entirely possible.

I went back and carefully looked at the email. And how it actually began was that Steve was in a restaurant and he looked over and saw Fred Hechinger. So, he went over to say hi because Steve liked his performance on White Lotus. As it turns out, Fred’s an actor who was on the Fear Street trilogy, and he’s apparently just about everywhere. I had no clue. He was just a good book club kid. So, thumbs up to book club kids. They’re awesome!

RVC: When did you decide to do the authoring and not just the curating, collecting, archiving, and everything else?

BB: When I was a kid, I wanted to be an author, but then I got older and I was like, “Oh, health insurance. Now what’s going to happen? I’m not going to become an author!” I didn’t take any writing classes or anything like that in college. So, I kind of put that on the side and I became a librarian. When I finally started thinking a little bit about it again, I had some ideas. Then Brandon Dorman, the New York Times bestselling illustrator, contacted me and was like, “Hey, let’s do a book together. You write it. I’ll illustrate it. I just want it to be about one thing–giants leaping up.” I was like, “You got it!” We wrote three books together and Greenwillow bought two. That’s how I became an author.

BB: When I was a kid, I wanted to be an author, but then I got older and I was like, “Oh, health insurance. Now what’s going to happen? I’m not going to become an author!” I didn’t take any writing classes or anything like that in college. So, I kind of put that on the side and I became a librarian. When I finally started thinking a little bit about it again, I had some ideas. Then Brandon Dorman, the New York Times bestselling illustrator, contacted me and was like, “Hey, let’s do a book together. You write it. I’ll illustrate it. I just want it to be about one thing–giants leaping up.” I was like, “You got it!” We wrote three books together and Greenwillow bought two. That’s how I became an author.

It’s a terrible story to tell because people want to know what blood, sweat, and tears you went through, and for me it was just a dude who was like, “Hey, you want to do something?” and I was like, “Yes!” so we did.

RVC: [Making Note to Self: become friends with bestselling, award-winning illustrators who might need authors to work with.]

BB: That’s just it–they don’t need authors. But I used to do a yearly roundup on my blog of who did the best middle grade book cover. Inevitably, it was him. He did a bunch of great covers. So, I guess he just figured I might be able to write a book?

RVC: Makes perfect sense to me!

BB: You are not, by the way, supposed to walk into a publisher with the author and illustrator, saying, “We wrote a book together!” They hate that. They like pairing authors and illustrators themselves. That’s how it works.

Do NOT walk in together.

RVC: Like you did?

BB: Like I did.

RVC: Let’s circle back on this librarian thing. What’s something that most writers wouldn’t know or appreciate about being a librarian?

BB: Excellent question. Back in the day, it would have been that not everyone who works in the library is a librarian. That gets some people all riled up and angry, like “I worked for two years on my Masters of Library and Information Science degree, and then you’ve just called any old person who’s here a librarian? Harrumph!”

Now, who cares? Call them a librarian.

Today, though, what they may not know, I suppose, is the degree to which we do social work. We have a social worker paid for by my city. At my library, we are very lucky–every library should come with its own built-in social worker, because we are not trained in social work. And we should be trained in social work, because we often deal with the same things. Even in the children’s book world, you got to deal with a lot of issues that you did not get taught when you went to your library school. And you didn’t have a class on this. Maybe these days they do. I don’t know.

RVC: Care to share an example?

BB: My first library job was at the Jefferson Market branch, a beautiful, beautiful location in Greenwich Village. Absolutely beautiful. And we had to deal with a very interesting set of clientele. One day, you might have to deal with a man with a sword. Here at my library in Evanston, we had to deal with a guy with a BAG of swords! We once had a guy with a parrot. He brought it in because he simply wanted to bring in his parrot. I also had kids set off a stink bomb in the children’s room, which was the most adorable tiny prank of all time–it was kind of cute.

But less adorable is the library branch where someone got attacked by a knife. You’ve got to know how to de-escalate. And, of course, every time there’s a weekday off of school, the library becomes the de facto daycare, right? Because parents who can’t afford to take off put the kids somewhere and they don’t want them at home. They think the library is the safest place, so they just drop them off. And some may or may not have lunch with them.

RVC: My goodness! Let’s talk about something happier, and what comes to mind is illustrators. You’ve had the good fortune of working with really fine ones, such as Dan Santat on The Great Santa Stakeout, and, of course, David Small on Long Road to the Circus. How’d you get so lucky as to work with big-time pros like them?

RVC: My goodness! Let’s talk about something happier, and what comes to mind is illustrators. You’ve had the good fortune of working with really fine ones, such as Dan Santat on The Great Santa Stakeout, and, of course, David Small on Long Road to the Circus. How’d you get so lucky as to work with big-time pros like them?

BB: First, I have to clarify something. Earlier, I said that you’re not supposed to walk in to a publishing house with your Illustrator. There’s almost never been a time I haven’t. Every time I do a book, I pretty much walk in with the illustrator which works when they’ve won Caldecotts. So for The Great Santa Stakeout, I wrote it and then gave it to my agent–who doesn’t do many picture books–and she was like, “Alright, who do we want to do the art?” I said “Dan Santat.” She said, “Go ask him.” So, I did. I told Dan, “Hey, man, I got a book. You want to do it?” And Dan, who’s completely booked up all the time said, “Can you wait two years?” I was like, “You betcha!” Lo and behold, he did it.

How I got to work with David Small is a little bit more of a story. As family lore has it, my grandma’s no-good uncle would skip out on his farm chores to walk over to an elderly ex-circus performer’s house to learn how to teach horses some circus tricks. Like you do.

RVC: Indeed.

BB: The woman’s name was Madame Marantette. And that woman’s house is currently owned by…David Small! When my mother learned this fact, she realized this family story that we all thought was jokey and silly was, in fact, true. And that this was something she had to tell me because it was actually kind of cool. I filed it away in my brain like, well, that’s neat. Later, I was like, “Man, what if I wrote a book that involved Madame Marantette, and maybe that uncle, and maybe some other things, and maybe David could do the pictures.” So, I wrote it as a picture book. To make a long story short, I showed it to David and he was interested, but said, “I see it more as a novel.” I’d never written a novel, but I did it, and David did spot art throughout. It worked out really well.

BB: The woman’s name was Madame Marantette. And that woman’s house is currently owned by…David Small! When my mother learned this fact, she realized this family story that we all thought was jokey and silly was, in fact, true. And that this was something she had to tell me because it was actually kind of cool. I filed it away in my brain like, well, that’s neat. Later, I was like, “Man, what if I wrote a book that involved Madame Marantette, and maybe that uncle, and maybe some other things, and maybe David could do the pictures.” So, I wrote it as a picture book. To make a long story short, I showed it to David and he was interested, but said, “I see it more as a novel.” I’d never written a novel, but I did it, and David did spot art throughout. It worked out really well.

RVC: Amazing. Thanks for sharing those stories. I’m now curious to hear about your work as a reviewer. What was it like the first time you had a review of yours in a big-time venue like The New York Times?

BB: That was a real thrill. I think I’ve reviewed for The New York Times twice. The first time was for Raina Telgemeier’s Smile, which nobody knew was going to blow up and be the biggest thing in the entire world. I just really liked it.

BB: That was a real thrill. I think I’ve reviewed for The New York Times twice. The first time was for Raina Telgemeier’s Smile, which nobody knew was going to blow up and be the biggest thing in the entire world. I just really liked it.

RVC: How’d you get that opportunity?

BB: I knew two New York Times editors just from living in New York–you just run into people at different events. And so I knew two of them. I’d already been writing my reviews in the style of a New York Times review, so it did feel very full circle to me to write for them, though it had a lot more pressure because they were actually fact-checking me, which nobody does. So, that was new, but they do a good job and were actually paying for it. They also asked me to review Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales: Donner Dinner Party.

RVC: You create some very good reviews. What’s your methodology for reviewing a picture book? For instance, what do you focus on? What do you think about? What’s your process?

BB: It really depends on the book. There are really good picture books out there that I can’t review. They’re great, and they might even be the best of the year, but when I sit down to review them, I can’t think of a word to say that would be original. Like “Book good, pictures pretty, story great.” Ugh.

RVC: As someone who’s been reviewing books for a half dozen years, I’ve been there.

BB: The book has to have a hook–there has to be something that I can hook the review on, something that I can say about it that’s new. So, I end up with eclectic choices in terms of the books that I reviewed if only because these are the ones that have given me something to say. That goes for any book, whether middle grade, or picture book, or board book–I can write five or even ten paragraphs on a board book if the board book gives me something to write about.

Someone once called me out for how I review picture books. They said, “You do the opening paragraph, then you do the summary of the book in the second one, and you have some thoughts, then you just do a concluding paragraph.” And to that person, I’m like, “Well, yeah.”

It’s funny because sometimes I write a review and I’m just like, “This is the best review!” And sometimes I do it and they’re not great. They might be very positive and people might be very grateful because I put lots of words into them. But they vary in quality like anything else.

RVC: What’s one thing that people maybe don’t fully appreciate about writing reviews?

BB: A review isn’t just if the book is good or bad. It’s asking questions like:

- What is the larger context of the book exists?

- What is the bigger picture?

- Why is this book different? (especially if you’re talking about picture books, where the sheer scads of picture books being published in a given year is just staggering–there’s just loads of them.)

- What does this book have to say about the world?

You know, in some way, what makes a book meaningful doesn’t have to be big. It could simply establish itself as important in this day and age in some fashion. Even if it’s like a goofy little book about a balloon that, you know, farts all the time. What does that say about fart books? There are lots of fart books. Walter the Farting Dog was a fart book. How does this new fart book fit in the ranking of fart books? Why do kids like fart books? What does a fart book do for a kid? Why do grownups hate fart books? There’s a bunch of stuff you can bring into this.

You know, in some way, what makes a book meaningful doesn’t have to be big. It could simply establish itself as important in this day and age in some fashion. Even if it’s like a goofy little book about a balloon that, you know, farts all the time. What does that say about fart books? There are lots of fart books. Walter the Farting Dog was a fart book. How does this new fart book fit in the ranking of fart books? Why do kids like fart books? What does a fart book do for a kid? Why do grownups hate fart books? There’s a bunch of stuff you can bring into this.

RVC: What do you do when you’re considering reviewing a book by someone you know?

BB: When I was young, I was a jerk. I didn’t care. I would tear a book asunder. Man, I got to tell you, if I can tear a book apart, it’s a thrill. But I haven’t torn a book apart in a while. I don’t know if this is because I’ve written books myself, or because I don’t want to be that jerk author who tears up other authors. When you’re the jerk LIBRARIAN who tears up books, that’s fine. That’s natural. That’s part of your job, so they can just dismiss it. But if you’re the jerk AUTHOR, you might end up in a publisher dinner with these people. I mean, they’re in the same boat as you, and it just feels trickier.

RVC: Agree completely.

BB: If a person I like does a book I don’t like, I don’t review it. I don’t mention it. I don’t put it in a roundup of any kind. I pretty much ignore it. That doesn’t mean that if they have a book that I’m ignoring that I necessarily dislike it. They’ll never quite know what my thoughts are unless I write up a Goodreads thing, which sometimes they notice (which isn’t healthy–don’t spend time reading all your reviews!).

There was a book out last year that I hated. I didn’t review it, though I really went back and forth on that decision. By all accounts, the author was the nicest person. And I thought about doing that review. This book didn’t win any awards. If it had started winning awards, I might have had to do a review of it and I really didn’t want to.

Once, there was a book I didn’t like that was literally number eight on Amazon. Now usually I don’t critically review a first-time author. But this book was number eight on Amazon and I didn’t like it. So, I did a negative review. That author wasn’t used to this kind of criticism and went off on my blog, and went off on their Facebook page. I don’t know this for a fact, but I think their publisher had them take it down on Facebook. But I didn’t take down their comment on my blog. That’s still up. Anyone can read it any time, and wow, were they mad. My little review somehow stuck them where it hurt. I was like, “Please, man, I’m not a drop in your ocean.” Yeah, that book is still popular to this day, so it shows what I can do!

RVC: Let’s talk about Fuse #8. How did this happen? And what do you get out of it?

BB: When I graduated from college, I had this 1989 Buick Century that my grandmother had given me because it was so ugly from sitting out in the sun all the time. She didn’t want it. So, free car. Awesome! And I parked the car one day, then took the key out, and the electric door locks went up and down and up and down. And up and down, up down. It was possessed. We called it Linda Blair. Unfortunately, it meant the electrical system was broken. I just graduated college, I had no job to speak of–I worked part-time for the summer for the Richmond, Indiana Symphony choir–so I was making no money. Still, I took it in to get it fixed. The mechanic could just see this person has no money, so he reached into the glove compartment and pulled out fuse number eight. “Look,” he said. “When you have it parked, just pull out this. It’ll stop your battery from getting drained.”

Now, fast-forward many years. My husband is a filmmaker, and at one point, he needed a name for his production company. He was having a hard time with an estate, so he wanted to call it Widow-Be-Damned Production, but no, we weren’t doing that. I suggested, “Fuse #8 Production. That’s catchy. It’s got a number in there. It’s got like a little hashtag. It’s awesome.” He didn’t think so. I thought I’d use the name someday, so when it came to name the blog, even though it had literally nothing to do with children’s books, I named it Fuse #8 Production, and it was catchy. There’s something to be said for a catchy name.

RVC: Great story. What do you like most about podcasting?

BB: It’s funny, I podcasted way back when I was in New York for a little while and I just couldn’t deal with the editing. I was like, “Too much editing! Not enough reason to do this!” So, no, I couldn’t. It was a lot of work. I thought about doing a one-woman show, but why?

When I moved to the Chicago area, my sister also moved back here. And when she did, I was like, I could do another podcast. But this time, I can make her do all the editing. I said, “Look, I know everything about picture books, while you know almost nothing. We’ll both go through a picture book each episode, and we’ll never run out. You can never run out of classic picture book. We’ll just do one per episode. You go out and read it, then you come back and we talk about it.”

She was like, “So, I’m the dumb one?” I told her, “No, you’re the innocent one.”

What do I get out of it? Sister bonding. I also host the Story Seeds podcast. And that one’s just really cool. I don’t do much except do the narration for it. I sometimes interview authors on that one. It’s just really fun.

RVC: Do you have a favorite episode? If someone’s never listened before, what’s a great starting place for each podcast?

BB: That’s a really good question. With the one I do with my sister, basically, you just need to find a book that you dislike and see what we think about it. If you hate Love You Forever, we might be the podcast for you. If you’re weirded out by Goodnight Moon, definitely check out our episode on that. Absolutely.

BB: That’s a really good question. With the one I do with my sister, basically, you just need to find a book that you dislike and see what we think about it. If you hate Love You Forever, we might be the podcast for you. If you’re weirded out by Goodnight Moon, definitely check out our episode on that. Absolutely.

In terms of Story Seeds. I mean, it’s got Jason Reynolds on there. So, you may as well just start at the top. It’s Jason Reynolds. It’s a cool episode.

RVC: What do you do if someone comes to you and says, “I want to write picture books.” What what would you recommend they do?

BB: That happens every other week. And I ask, “Are you familiar with the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators? Because if you’re not, this is an organization that you should consider joining, or at least attending a couple meetings of to get a feel for. They can really help you as you’re working out what you want to do and what you want to make.”

You do not say, “Oh, show me your manuscript!” because people like to use librarians as free book editing advice. Only once in a while did we see really good ones when I was on the desk. There was one which had seven-foot-tall puppets made out of masking tape. Oh, the creepiest thing you ever saw.

First and foremost, though, I recommend SCBWI, and there’s the annual Children’s Writer’s & Illustrators Market Guide book. We always have a copy here that people can look at. But it’s mostly do your research and read books you like. If you want to write a picture book, find other picture books like yours and read them. Get a sense of what’s out there. Do your homework and ask questions.

RVC: We here at OPB are a big fan of Jane Yolen. We did a big To-Do about her 400th published book when it came out not that long ago. What’s your favorite book of hers?

RVC: We here at OPB are a big fan of Jane Yolen. We did a big To-Do about her 400th published book when it came out not that long ago. What’s your favorite book of hers?

BB: It’s not exciting. Owl Moon. In fact, it’s the boringest answer I could give since it’s her Caldecott winner, but I recently talked about it on my podcast with my sister. The book holds up. The writing holds up. The owl holds up. The whole darn kershmazel holds up.

RVC: The owl does, indeed, hold up nicely. Now…one last question for this part of the interview. What are you working on next?

BB: I’m working on another novel.

When I was younger, all these authors like Robert Newton Peck and Richard Peck–pretty much anyone with the last name Peck–was doing these nostalgic books, like Ray Bradbury with Dandelion Wine. Where are the nostalgic books for the 80s with the Pocket Rockers and the Pogo balls and He-Man? Doggone it, it was the last gasp before the internet took over everything, right? And so I’m writing the most ridiculous book. It’s just stories and a lot of it’s based on my youth. And it’s so fun, so enjoyable.

When I was younger, all these authors like Robert Newton Peck and Richard Peck–pretty much anyone with the last name Peck–was doing these nostalgic books, like Ray Bradbury with Dandelion Wine. Where are the nostalgic books for the 80s with the Pocket Rockers and the Pogo balls and He-Man? Doggone it, it was the last gasp before the internet took over everything, right? And so I’m writing the most ridiculous book. It’s just stories and a lot of it’s based on my youth. And it’s so fun, so enjoyable.

RVC: What’s the target audience?

BB: 9 to 12, though it could go younger. I’m basically trying to tap into that kind of Calvin-and-Hobbes-in-their-backyard-in-the-woods type of feel, where it’s just kids running around with no parents because that’s how it was at the time. I tell my kids how when I was a kid, my parents were like, “Here’s a sharp rusty nail and a brick, go play.” That was parenting in the 80s. “And come back at dinnertime!”

RVC: Okay, Betsy, it’s now time for…THE SPEED ROUND. The point values are quadrupled, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. Let’s zoom through these final six questions. Are you ready?

BB: As prepared as I can be!

RVC: Best place in Evanston for Chicago-style pizza?

BB: Union Pizza.

RVC: Favorite drink and/or snack for a late-night reading session?

BB: I’m horribly addicted to iced chai latte from Starbucks. And their brownies, too, which no longer have espresso beans, but I forgive them.

RVC: What’s a secret talent you have?

BB: Oh, I can spin on a spinning wheel. If you give me a spinning wheel and you give me some roving (wool), I can give you yarn.

RVC: What’s the best picture book you’ve read this year?

BB: The first one that just pops into my mind–maybe it’s not the best of the year, but it’s near and dear and close to my heart–is Off-Limits by Helen Yoon. And it’s a great readaloud. Man, I could read that thing aloud so well! It’s a COVID book to a certain extent. It really caught me by surprise. It’s only like her second picture book, but it’s a delight.

BB: The first one that just pops into my mind–maybe it’s not the best of the year, but it’s near and dear and close to my heart–is Off-Limits by Helen Yoon. And it’s a great readaloud. Man, I could read that thing aloud so well! It’s a COVID book to a certain extent. It really caught me by surprise. It’s only like her second picture book, but it’s a delight.

RVC: What’s an underappreciated-but-great picture book?

BB: A really good question. Someone who doesn’t get enough attention is Keiko Kasza. My Lucky Day is one of the greatest readalouds of all time. Yeah, I said it. It’s amazing. That book does not get enough respect.

RVC: That pig is just so clever.

BB: Seriously, right? And how many picture books can you think of with a narrator you can’t trust? It’s a great book.

RVC: What’s the most memorable kid + picture book experience you’ve been part of?

BB: There was a kid who was obsessed with getting a certain book in my library. And he tromps up to me. Oh, this kid has clearly explained it 100 times to other adults because he’s like, “I need the orange book. It’s the one about the woman and she’s got the white hat. She’s NOT a pilgrim. And there’s baby Jesus. And there’s a baker.”

I ask: “Is there anything else?”

The kid says, “There’s a pasta pot.”

Me: “Is it Strega Nona?”

The Kid: “YEEESSSSS!”

Oh, yeah. There’s the baby Jesus. And there’s Strega Nona, who is not a pilgrim. And she’s got a white thing on her head–I’ll give you that!

RVC: Thanks so much for doing this, Betsy. This was a total and complete hoot of a good time.

Saguaro’s Gifts

Saguaro’s Gifts

This month’s Industry Insider interview is with a name you likely know well–author, librarian, blogger, podcaster, and reviewer Betsy Bird. Welcome, Betsy!

This month’s Industry Insider interview is with a name you likely know well–author, librarian, blogger, podcaster, and reviewer Betsy Bird. Welcome, Betsy!

Please welcome Julia Kuo to

Please welcome Julia Kuo to