It’s with great pleasure that I introduce Andrea Spooner, this month’s Industry Interview subject. Andrea’s the Vice President and Editorial Director of Picture Books at Little, Brown Books for Young Readers (LBYR). When I realized her imprint won a Caldecott Medal three years in a row, I knew I needed to find out a bit more about what kind of picture book magic they were cooking up there.

Here’s a bit about her. After joining LBYR in 2003, she’s worked with an amazing list of authors, including:

She’s also edited dozens of James Patterson’s books. What impresses me most of all, though, is how the people she works with rave about her. Consider this endorsement, from writer Crescent Dragonwagon: “Andrea took a lot of time finding just the right artist, and she is taking a lot of time working with him, and me. In 40 years of working with different publishers, I can remember no other children’s book editor who has ever involved me quite so much in the selection of the artists, and has engaged me so thoughtfully in discussing the pictures and my reactions to them.” And she adds that Andrea is “one of the most attentive and respectful editors I have ever had.”

Wow.

With that, let’s get on to the interview!

RVC: For some, working in the kidlit business seemed destined in the stars from the start. For others, it’s a curious accumulation of events that brought them to that future. Which was it for you?

AS: Destined from the start! My mother was an artist and art historian, and my father was an English professor with a focus on writing short stories. I read voraciously and wrote prolifically as a child. The first long-form story I wrote and illustrated, at age six, was called The Girl Who Hated School, followed up by an “illustrated novel” called Nancy and the U.F.O.! So, I always wanted to make books. I loved the interaction of picture and word… and nothing ever moved me like the books I read as a kid. I even wrote my college application essays about the Nancy Drew series as well as my favorite book of all time, Freaky Friday by Mary Rodgers. I guess it was a clear sign I took kidlit seriously from the beginning.

AS: Destined from the start! My mother was an artist and art historian, and my father was an English professor with a focus on writing short stories. I read voraciously and wrote prolifically as a child. The first long-form story I wrote and illustrated, at age six, was called The Girl Who Hated School, followed up by an “illustrated novel” called Nancy and the U.F.O.! So, I always wanted to make books. I loved the interaction of picture and word… and nothing ever moved me like the books I read as a kid. I even wrote my college application essays about the Nancy Drew series as well as my favorite book of all time, Freaky Friday by Mary Rodgers. I guess it was a clear sign I took kidlit seriously from the beginning.

RVC: My kids wore out the DVD version of Freaky Friday with Jamie Lee Curtis, Mark Harmon, and Lindsay Lohan. But prior to that, I recall liking that book a great deal myself!

What were some of the key elements/choices of your life that prepared you to be an editor?

AS: The most significant choice leading me toward my career might have been the day in seventh grade when I decided to join Yearbook Club, even though I was told it was only for eighth graders. Turns out just showing up with genuine commitment was more important than my age, and before the year was out I was editor-in-chief.

RVC: As former Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli famously said, “History is made by those who show up.”

AS: Editing the yearbook took over my life all the way through college. And perhaps choosing to go to Smith College, known for breeding kidlit folk, prepared me for this editing life! At Smith, I was a studio art major and writing minor, and there’s nothing quite like all those group critique sessions to prepare you for the task of gently sharing feedback.

RVC: Let’s talk recent picture book projects. What’s on the docket for 2020 that has you excited?

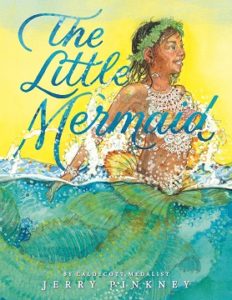

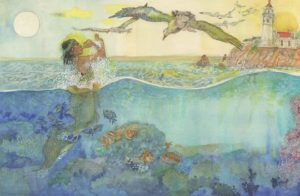

AS: Oh dear, it’s like you’re asking a mother to talk about her favorite child—it’s inherent betrayal not to speak of all of my books! I’m asking the universe to forgive me in advance for not mentioning the entire LBYR picture book list. But I don’t think anyone would begrudge me for sharing my intense excitement for Jerry Pinkney’s next brilliantly-illustrated retelling! It’s The Little Mermaid… and it’s the first major picture book version that reinvents the story as a friendship story instead of a romance, and that features a cast of mermaids with brown

AS: Oh dear, it’s like you’re asking a mother to talk about her favorite child—it’s inherent betrayal not to speak of all of my books! I’m asking the universe to forgive me in advance for not mentioning the entire LBYR picture book list. But I don’t think anyone would begrudge me for sharing my intense excitement for Jerry Pinkney’s next brilliantly-illustrated retelling! It’s The Little Mermaid… and it’s the first major picture book version that reinvents the story as a friendship story instead of a romance, and that features a cast of mermaids with brown  skin. It also leaves readers with the critical message that you should never give up your voice for anything. I think it has potential to become the most definitive contemporary reimagining of the story.

skin. It also leaves readers with the critical message that you should never give up your voice for anything. I think it has potential to become the most definitive contemporary reimagining of the story.

RVC: With books like that coming out from LBYR, I get a real sense why you’ve got that incredibly impressive 3‑peat of Caldecotts going. But I’ll ask anyway–to what do you attribute that streak of success?

AS: Do you mean when LBYR won a Medal three years in a row in 2015–2017? Or… do you mean last year in 2019 when we took three out of the five stickers?

Okay, okay, I don’t mean to sound smug, but yeah, we’re kind of proud of the track record. What I’m most proud of is that these stickers are on books with many different artists and editors and art directors. There’s not just one superstar on the list. It’s really about strong teamwork, I think. There are a lot of eyes on the project, from acquisition through creative development, and everyone on the team is very invested from day one. We also have a fantastic school & library division making sure the books get in front of all the right people at the right time.

RVC: Speaking of 3s, you personally edited three Caldecott winners as well. Coincidence?

AS: I’m exceptionally lucky! It helps when you’re working with bona-fide geniuses like Jerry Pinkney, Patrick McDonnell, and Oge Mora, who all have pretty powerful and sophisticated creative muses. And I wouldn’t be working with them if it weren’t for the intercession of my former mentor David Reuther, former LBYR editor Amy Lin, and art director Sasha Illingworth, so I can’t take credit for actually discovering this incredible talent.

If I ever make a difference in elevating work to a sticker-worthy level, it’s likely derived from my willingness to question a choice that’s being made and to push the author or artist to justify it, even the seasoned people. But I’m also willing to step back and let the artist’s muse be the voice in charge. The trick is figuring out when the time is right for each!

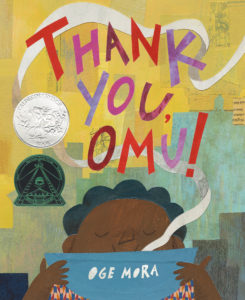

RVC: I was pleasantly surprised to find that you edited one of my fav picture books of 2018, Thank You, Omu! How did that project come into being?

AS: It’s such a happy story! One of our art directors, Sasha Illingworth, was providing critiques at the Rhode Island School of Design in a picture book-making class, and she came back recommending that editors take a look at several of the students’ final projects, which really impressed her. Oge’s project, Omu’s Stew, was at the top. It was clear from the start that Oge had a remarkable handle on the totality of what makes a great picture book, and that it came naturally to her. We offered her a two-book deal while she was still a senior in college.

AS: It’s such a happy story! One of our art directors, Sasha Illingworth, was providing critiques at the Rhode Island School of Design in a picture book-making class, and she came back recommending that editors take a look at several of the students’ final projects, which really impressed her. Oge’s project, Omu’s Stew, was at the top. It was clear from the start that Oge had a remarkable handle on the totality of what makes a great picture book, and that it came naturally to her. We offered her a two-book deal while she was still a senior in college.

RVC: That’s an inspiring story for sure! What’s it like working with such an early-career talent? What kind of different considerations do you have with them versus, say, working with a mid-career or senior-level creative?

AS: I think the way I work is mostly unrelated to how long the creator has been in the business. Of course, with debut talent I try to make sure that I take more time to explain the stages of the publishing process, and the vocabulary and quirks of it. Ultimately, though, each creator has individual needs that aren’t related to where in their career they are. I first try to get a sense of what their goals for the project are, figure out what makes their creative heart ticks, and learn what kind of managing or mentorship they need to generate their best work. Sometimes that involves trial and error, for sure. For me, with a new author it can take longer to figure out the key to a smooth creative process. After I’ve worked with someone once or twice, it’s easier to keep the author or artist happily engaged, productive, and open to feedback.

RVC: You’ve talked about how one of the many tasks of an editor is to improve the read-aloud experience. What are some specific ways that can happen?

AS: We start by reading that manuscript aloud. Authors can do this too as they write and self-edit. If you find yourself tripping on certain word/sound combinations or sentences, rewrite it or cut it. Better yet, have a few others read the manuscript aloud and flag any patterns of stumbling. Reading the text aloud also gives you a sense of where the pacing feels too slow. Sometimes I find myself looking forward to the end of a sentence, paragraph, or page. That might be the sign of an area that can be tightened. I want to feel like I’m relishing each word.

RVC: With my fav picture books, that’s exactly it. “Relishing each word.”

AS: And, of course, we think about the page turns—they’re an essential part of the read-aloud experience. Those dramatic pauses should be intentionally placed. They propel you through the narrative, and can leave you with an underlying question about what’s going to happen next. I always start editing by paginating a text, since helps me focus on the read-aloud experience.

RVC: At LBYR acquisitions meetings, are picture book manuscripts actually read aloud? Does everyone have a copy in front of them, too?

AS: Reading the book aloud would be part of my fantasy vision of an acquisitions meeting—I’d love to know if any houses actually do that! But, it’s essential that everyone reads and thinks about acquisitions materials ahead of time; there would rarely be time to perform the books live in such meeting. At LBYR, editorial directors for each genre under consideration are expected to have vetted the manuscript for its viability prior to putting it on the agenda. And sometimes, read-aloud quality emerges later in the editing and polishing process. So, the manuscript might not even have a perfect “mouthfeel” at acquisitions stage, but it has enough other exciting qualities to motivate us to make an offer.

RVC: So much of the submission process is a matchmaking game that can feel like blind luck, at times. Let’s help some people out here. What are a few likes/dislikes of yours in terms of themes, subjects, and/or styles?

AS: As an editorial director, I’ve trained myself to look beyond my own personal likes and dislikes when considering if a project is right for the LBYR list. We need a diverse portfolio in all respects in order to survive and thrive. As an example, I used to say “don’t send me lovey-dovey books”, but nowadays, I’m totally open to them. I’m better able to look beyond the genre and think “are there audiences out there that like this and want this? Is the market for this kind of thing underserved, or do we have a gap on our list for it?” Some people might say it’s freeing to get to the point in your career when you’re at liberty to only work on the books you personally adore. For me it’s been the opposite–it’s actually been really freeing to embrace things I wouldn’t have necessarily purchased for my own collection.

Is that a cop-out answer?

RVC: Well…

AS: Okay, okay, I’ll give you this much: For personal projects, right now I’m dreaming of silly-but-smart stories that scratch the itch we all have to laugh more in our increasingly troubled world. I tend to be drawn to absurdist humor. Science and nature/environmental themes often resonate with me. I’m also keen on books that address important moments of child development, and I’m currently seeking more stories that feature differently-abled characters from authentic perspectives. I’m also always looking for substantive stories with strong voice, re-readability, and emotional resonance. For art, I look for work with a “signature style.” Once a style becomes trendy and ubiquitous, I’m less stimulated by it.

RVC: Beyond any issue of theme, subject, or style, what are your submission pet peeves?

AS: Manuscripts accompanied by an eternally long pitches and story summaries that are longer than the story itself. Give me one really strong paragraph about the market viability and comparative titles, and if there’s an interesting backstory to the story or connection to the author’s life, that can be another tight paragraph. Also, if we want to get petty for a moment, I’m put off by manuscripts that are single-spaced!

RVC: I’m so glad you said that. I’ve been telling students for years to keep on double-spacing their submissions, and I’m not sure they believe me. Now I have proof!

AS: By the way, including art notes in a picture book text is absolutely not a pet peeve of mine. So many picture book writers have been told not to do this. But to me, I like to know that a writer has a sense of how visual storytelling impacts a narrative and how they intrinsically work together. A writer shouldn’t be wedded to their proposed vision, but they could convey it at pre-acquisition for the sake of transparency, and sense. You have to remember that the non-editorial folks like sales and marketing who are a part of the acquisition conversation may not have the same visual literacy or imagination as an author—and even the best editors aren’t capable of reading an author’s mind! But I am perfectly capable of removing art notes from a manuscript after acquisition if I think they’ll impede an artist’s own personal vision.

RVC: Lots of kidlit industry folks spend a lot of time on social media and their web presence. You seem less concerned about that. Is that a choice or the effects of being so busy with work that it’s on the perpetual back burner?

AS: Thanks for shooting that arrow right into my Achilles heel, Ryan!

RVC: Is it really an Achilles heel?

AS: Sometimes I think it is, but I have complicated feelings about it. I unequivocally admire with awe and wonder those many editors who consistently produce high-quality books, manage robust lists, and maintain a vibrant social media presence. I’ll never be one of them, and it’s probably a personal failing of mine, but I have to embrace what I’m best at and make the most of it. We have a fantastic marketing department to publicize the authors and books. My “brand,” if I must have one in this day and age, is about what I do behind the curtains rather than what I’m saying on the public stage.

RVC: Let’s talk about that behind-the-curtains stuff.

AS: Here’s the thing: I spend or eleven or twelve hours a day largely in front of a screen. I don’t want to spend one minute more. This time and energy, for me, is best spent working for my authors, managing projects as seamlessly as possible, shaping the list and mentoring staff. I consider myself not just an editor, but a customer service representative—and I say that in all seriousness! My number one goal is for everyone, externally and internally, to feel like the process went off as smoothly as possible, and that we made a book we couldn’t have done better… without the benefit of hindsight, anyway.

I haven’t yet found a way to do all that and spend time sorting through the daily mess of social media and maintain my own polished social presence in a way that would meet my own standards. Frankly, I’m really not good at expressing any worthwhile thought in 140 characters or less, as you can see from this interview! There’s too much unnecessary chatter out there as it is. I see myself doing the world a service by not adding to it.

RVC: I typically keep my questions focused on picture books, but my kids LOVED the Patterson Middle School series, so I have to ask something about him. He’s so prolific that I’m inclined to ask how many James Pattersons there are! But I’ll assume there’s just one (unless you secretly tell me otherwise).

RVC: I typically keep my questions focused on picture books, but my kids LOVED the Patterson Middle School series, so I have to ask something about him. He’s so prolific that I’m inclined to ask how many James Pattersons there are! But I’ll assume there’s just one (unless you secretly tell me otherwise).

Here’s an actual question about him, though–in all your experience in working with him, what has surprised you the most?

AS: That he is the real deal in every respect. He’s just one person, yes, who’s deeply connected to every book with his name on it—he’s not rubber-stamping anything. There’s no team of people inventing the core stories; he drafts every single outline, and even the kids’ book outlines we worked on together were about 50 pages long, so there’s a lot of detail. He’s always at his desk working. Over the course of a dozen years of working together I could probably count on one hand times I called him that he didn’t pick up the phone. He’s genuinely passionate about writing, and promoting the pleasure and excitement of reading, which is what motivated his move into kids’ books. There’s nothing he’d rather being doing than writing. Except occasionally playing golf or watching a movie. I also learned a lot from Jim about the craft of commercial writing, especially when it comes to the emotional experience of reading. But those are trade secrets I can’t give away!

RVC: Alright, it’s time for the final part of the interview. The always-surprising, often-quippy, ever-zippy LIGHTNING ROUND. Are you ready?

AS: Of course not! Have you not yet noticed that quips are not my specialty? Remember what I said about being able to say anything in 140 characters or less?

RVC: Don’t overthink it.

AS: That’s what my bosses always say on my performance reviews. Okay, let’s try it!

RVC: Star Trek, Star Wars, or Stargate?

AS: Star Trek! I mean… Leonard Nimoy, George Takei, Nichelle Nichols… and quantum teleportation!

RVC: Secret hobby you have that no one would suspect?

AS: Will anyone know what pysanka is?

RVC: Probably not. Let’s save them from having to Google it, though.

AS: It’s the art of making Ukranian Easter eggs with old-world tools like a wooden/metal stylus, beeswax, an open flame, and dyes. Mine are not anywhere near as good as what you see on Wikipedia.

RVC: What four picture book characters do you invite over for Sunday afternoon smoothies at the Spooner house? What’s your dream lineup?

AS: Well, if it’s Sunday afternoon in our little apartment, they’d have to be very well-behaved! So I think Rosie Revere, Ada Twist, Sofia Valdez, and Iggy Peck would fit make for some very scintillating conversation. My other favorites are way too naughty.

RVC: Hardest venue to get a starred review?

AS: I can’t remember the last time I got a star from The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books. I don’t lose sleep over it.

RVC: Coolest non-LBYR picture book of 2019?

AS: Hmmm, when it comes to “cool” I think the Melissas have it, for me—I’m debating between The Balcony by Melissa Castrillon and How to Read a Book by Kwame Alexander and Melissa Sweet. The art for both books just vibrates with energy, passion, and endless detail.

AS: Hmmm, when it comes to “cool” I think the Melissas have it, for me—I’m debating between The Balcony by Melissa Castrillon and How to Read a Book by Kwame Alexander and Melissa Sweet. The art for both books just vibrates with energy, passion, and endless detail.

RVC: Three words that sum up your picture book philosophy.

AS: Aw, that’s just cruel. I am not a woman of brevity…

RVC: Give it a shot!

AS: Read. It. Again.

RVC: Thanks so much, Andrea!

And for you artistic OPB fans out there, here’s a LBYR public service announcement. They’re starting their fourth year of the Emerging Artist Award. Their first winner just had their book published and it won a New York Times Best Illustrated Book of 2019 honor, so the future seems bright for these winners. Consider applying–perhaps you’ll soon be working with Andrea or one of her amazingly cool colleagues!

This month’s interview is with Elisha Cooper, an author who both writes and illustrates his own picture books. Instead of doing a standard bio paragraph here, let’s begin the process of getting to know him and his work a little bit better via two lists.

This month’s interview is with Elisha Cooper, an author who both writes and illustrates his own picture books. Instead of doing a standard bio paragraph here, let’s begin the process of getting to know him and his work a little bit better via two lists.

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press,

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press,