**Thanks to picture book author Dianne Ochiltree for stepping in to be the guest interviewer this month!**

Meet Emma D. Dryden, founder and principal of drydenbks, a premier provider of editorial and coaching services for the children’s publishing industry. Prior to her role as guiding light at drydenbks, Emma was a children’s book editor–first at Random House Children’s Books, and next at McElderry Books, an imprint of Macmillan Children’s Books, where she worked with the legendary Margaret K. McElderry. After Ms. McElderry’s retirement, Emma was made Vice President, Editorial Director of the imprint; in 2005 she became Vice President, Publisher of Atheneum Books for Young Readers and Margaret K. McElderry Books, imprints of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing, a position she held until 2009 when she launched drydenbks.

Meet Emma D. Dryden, founder and principal of drydenbks, a premier provider of editorial and coaching services for the children’s publishing industry. Prior to her role as guiding light at drydenbks, Emma was a children’s book editor–first at Random House Children’s Books, and next at McElderry Books, an imprint of Macmillan Children’s Books, where she worked with the legendary Margaret K. McElderry. After Ms. McElderry’s retirement, Emma was made Vice President, Editorial Director of the imprint; in 2005 she became Vice President, Publisher of Atheneum Books for Young Readers and Margaret K. McElderry Books, imprints of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing, a position she held until 2009 when she launched drydenbks.

Over the course of her career Emma has edited more than 1,000 books for children and young readers. As publisher, she oversaw a staff of editors and the annual publication of over one-hundred hardcover and paperback titles. The books she’s edited have received numerous awards and honors, starred reviews, were named to year-end “best of” lists, received regional and national publicity and acclaim, and hit the bestseller lists in USA Today, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Publishers Weekly, and other national publications.

So, who better to ask questions about picture books, children’s publishing, and everything bookish? Let’s go!

DO: What first attracted you to children’s publishing?

EM: Long before I majored in English Language and Literature in college, I was an avid reader and book-lover. I thought about becoming a writer, but decided I’d rather be immersed in lots of different kinds of stories and lots of different kinds of writing, which made me think I could enjoy being an editor working with all kinds of writers. I was particularly drawn to children’s publishing because I never outgrew my love for illustrated books. To be honest, I have never really outgrown that aspect of my childhood in which I found great solace and comfort in books, which is why I still adore reading children’s books—especially picture books and middle grade.

DO: What about the children’s publishing industry has kept you engaged in it for all these years?

ED: I was lucky to be hired by fantastic editors who became mentors and friends; and I quickly felt—and continue to feel—a kinship and shared spirit with people in all aspects of the children’s publishing industry. I love the range of topics, categories, genres, voices, styles, and shapes of children’s books and thrive on the marvelous variety of books and projects on which I’ve been able to work throughout my career—working on a picture book, a MG novel, and a poetry collection one day; working on a YA novel, a board book, and a graphic novel the next.

DO: What was it like working with legendary Margaret K. McElderry?

ED: Margaret was a tremendous editor from whom I learned so much, from how to reject a manuscript with sensitivity and how to get the best out of an author by posing thoughtful questions during the editing process, to how to conduct oneself professionally and never forgetting to take time to laugh. Margaret was tough—she had to be; it was her name on the spines of those books! She also had such a lovely and sharp sense of humor. She was an inspiration to me in so many ways and I am ever grateful our paths crossed in the ways they did.

DO: How has the picture book form, and the industry itself, evolved in the years of your career?

ED: This is an interesting question insofar as my first thought is that the picture book form hasn’t really changed all that much—not when it comes to the basic “mechanics” of a picture book being 32 or 40 pages with or without endpapers, relying on page turns to create tension and an impetus for a reader to find out what happens next, being illustrated in a way that expands and deepens the text, and so forth. The picture book industry itself is always evolving and growing and picture books can afford terrific opportunities for authors and illustrators to really play with language, perspective, boundaries, voice, and more. It’s these elements that I see ever evolving as picture book creators experiment and apply new ways of storytelling and new ways of engaging young readers.

DO: What services do you offer to authors, publishers, and agents?

ED: drydenbks LLC provides editorial and creative services to children’s book authors, illustrators, publishers, and agents. Over fourteen years this has included engaging in consultancy and coaching services with authors about their manuscripts, evaluating a small press’ publishing goals and brainstorming how to expand or focus their program, assisting authors sent to me by their agents to ready their manuscripts for submission, helping illustrators update and energize their websites as they prepare to query agents, explaining the ins and outs of children’s publishing to potential publishers, and leading workshops or retreats about different aspects of the writing and revision process.

ED: drydenbks LLC provides editorial and creative services to children’s book authors, illustrators, publishers, and agents. Over fourteen years this has included engaging in consultancy and coaching services with authors about their manuscripts, evaluating a small press’ publishing goals and brainstorming how to expand or focus their program, assisting authors sent to me by their agents to ready their manuscripts for submission, helping illustrators update and energize their websites as they prepare to query agents, explaining the ins and outs of children’s publishing to potential publishers, and leading workshops or retreats about different aspects of the writing and revision process.

DO: Can you describe your ideal picture book client?

ED: The ideal picture book client is the author or author/illustrator who has not only worked on writing and revising (and revising and revising) their manuscript or dummy, but who has spent time studying how picture books work so they fully appreciate the importance and purpose of the page turn, the importance of leaving a lot unsaid in the text that can be expressed through illustrations, and who is fully open to new ideas and perspectives about their work for the sake of making their project truly sing.

DO: How can potential clients best prepare for their work with you, so they—and you—can get the most from the critique and coaching experience?

ED: Ideally, I prefer to work with clients who have completed manuscripts—and not simply first drafts, but multiple drafts; clients who have revised their work as much as they can on their own. I don’t hold back in my critiques—so the ideal client is someone who has spent time before they contact me learning about children’s publishing, learning about the category and genre in which they’re writing, and understanding what to expect from a professional critique. Those who have been through some sort of critiquing and workshopping before they work with me are usually more open to entertaining new perspectives and ideas about their work and exploring the kind of provocative “what if?” suggestions and questions I like to pose—and that makes our work together richer and more productive.

DO: What do you think is a key element to crafting an excellent picture book manuscript?

ED: Picture books are a wondrous collaborative art form. Words and illustrations must harmonize—each bringing their own personality, emotion, and mood to create a memorable harmony. It’s important for picture book authors to understand and be excited by the fact that illustrators will not be putting their exact words into pictures in a literal interpretation, but will be adding a whole other level of story to their words. I encourage picture book authors to think of their texts as the musical score that accompanies a drama we see upon a stage. And so saying, the musical score of the picture book needs to be poetry, subtle, emotional, and not overblown–not so loud that it drowns out the drama that will be enfolding on the pages through the artwork.

DO: How do you think picture book authors and illustrators can meet challenges they might experience during the writing/submission/ agenting/publishing process?

ED: So, first off, I will say authors and illustrators WILL without a doubt experience challenges all along the way from story concept inception through publication and even into the aftermath of publication. The breadth and depth of these challenges will vary depending upon so many factors that are without or within a person’s control, including an individual’s personality, experience, background, artistic process, support system, goals, expectations, life changes, definition of success, someone else’s rules, and more. It’s not easy to generalize, of course, but one thing I will say I’ve learned over the course of my long career in this business—a business which has always had ups, downs, highs, and lows—is that the best way to get through challenges is for an author or illustrator to figure out ways to keep going with their creative work and to truly honor their creative work—in whatever form that takes. That could mean grabbing just ten minutes a day for some sort of creativity, finding a new form of support system, getting out of your comfort zone to try something new, taking a class, scripting a tough conversation you know you need to have, asking for help, and above all, giving yourself grace.

In crafting a story—nearly any story, really—a main character can’t evolve or grow without facing challenges. Conflict is what propels a story, a main character, a reader forward to find out what happens. So too in our own lives, right? The more we can figure out how best to face, manage, and learn from challenges, the more we will be able to grow and evolve. It’s not easy and sometimes completely new paths will have to be forged, but I urge authors and illustrators to remember that what they always have is their creativity and their ideas—and these are worth nurturing even through the hardest challenges.

DO: In addition to your work as editorial consultant, you’ve written poetry, essays, and articles for industry publications. How does your experience as a writer influence the work you do with authors?

ED: Writing and revising my own work—on a deadline—has made me appreciate how hard writing and revision—on or off a deadline!—can be. Spending time, energy, and emotional grit on my own writing reminds me how important it is as an editor and coach to respect and empathize with what authors and artists do—and never to take any aspect of the creative process for granted.

DO: Editing, consulting, coaching, writing—whew! You are a busy entrepreneur. What do you like to do in your downtime?

ED: I don’t have the healthiest work-life balance (show me any self-employed person who does!), but when I can, I love spending time with friends, being outside in nature, and traveling—particularly to places with loads of animals and fascinating land- or seascapes.

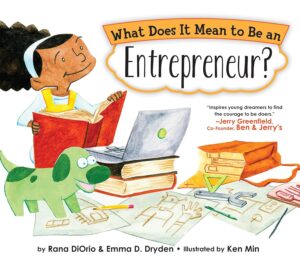

DO: Speaking of entrepreneurs, you have co-written a wonderful picture book titled What Does It Mean to Be an Entrepreneur?, published by Sourcebooks/Little Pickle Press in 2016. Can you tell us how that project came about?

ED: I’d worked with author and entrepreneur Rana DiOrio for quite a while before we co-wrote our book. I’d been editing some of the books Rana was publishing at Little Pickle Press and we were talking about adding a title to her What Does It Mean to Be…? series about entrepreneurship. Not an easy or accessible subject for picture book age readers, to be sure—and after seeing some writing/outline samples that we didn’t think were working, I jokingly said “We could write this book ourselves!”—and Rana took me seriously. So we gave it a try.

ED: I’d worked with author and entrepreneur Rana DiOrio for quite a while before we co-wrote our book. I’d been editing some of the books Rana was publishing at Little Pickle Press and we were talking about adding a title to her What Does It Mean to Be…? series about entrepreneurship. Not an easy or accessible subject for picture book age readers, to be sure—and after seeing some writing/outline samples that we didn’t think were working, I jokingly said “We could write this book ourselves!”—and Rana took me seriously. So we gave it a try.

Our collaboration was tremendous fun, both of us bringing years of experience as entrepreneurs and picture book experts to the process. We created a spare text which at first glance seems to be a string of disparate general ideas, but which we wove together by coming up with a strong visual narrative storyline for the book. It’s in the illustrations where a main character and plot could come alive to pull our ideas all together. We shared our vision with the oh-so-talented illustrator, Ken Min, who completely got it and the book was born. I’m very proud of that book!

DO: What is your one best piece of advice for all our author friends out there?

ED: Can I give two pieces of advice?

DO: Sure!

ED: Take plenty of time between drafts of your work. Don’t underestimate the writing and revising of your story that goes on in your subconscious mind between drafts. It’s necessary and important!

Whether or not publication is your goal, keep writing for the sake of writing and then ask yourself how you define “success” when it comes to your writing. If you attend workshops, retreats, and webinars and are members of groups like Highlights Foundation, SCBWI, or WNDB, you will be hearing a lot about other authors’ processes, goals, dreams, and projects. That can be inspiring, but it’s important for you to recognize and nurture your specific processes, goals, dreams, and projects. I ask workshop attendees to fill in the blank: “I have to write this story because I ________.” I urge your readers to complete this exercise and keep the responses somewhere you can see them. Never lose sight of why you’re writing what you’re writing.

DO: You are also an accomplished speaker, teacher, and workshop presenter on all aspects of the business and craft of writing for children. What do you most enjoy about this aspect of your work?

ED: Sharing my knowledge, expertise, and ideas about writing and revising with authors comes easily to me and I love the conversations and creativity that result. It’s also fun to share my “insider” knowledge about the children’s publishing business. I particularly enjoy the give-and-take with authors in a workshop or retreat setting, the exchange of ideas, the asking and answering of questions, and the “ah ha!” moments that always come for authors/illustrators who are engaging deeply with their work in a nurturing, supportive environment. It’s gratifying to feel helpful and be allowed a gentle glimpse into people who are tapping deeply emotional places as they create their manuscripts and projects.

DO: And how can readers find out about where you are appearing in the future?

ED: I don’t announce appearances on my website or have a calendar that people can follow. I do post about workshops, retreats, or webinars on Facebook and sometimes on my sometime-blog, so I hope people will follow me on those platforms.

I am happy to share with your Only Picture Books audience that I will be co-leading a Revision Retreat at the Highlights Foundation on November 14–17.

DO: You generously share information about children’s literature, the craft of writing for children, and the business side of children’s publishing on social media. Where can readers find and follow you?

Website: https://drydenbks.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/emmaddryden and https://www.facebook.com/drydenbks

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/emmaddryden/

My sometime-blog, “Our Stories, Ourselves”: https://drydenbks.com/blog/

DO: One final question. What are three things that OPB readers would be surprised to learn about you?

ED: That’s a fun one! Let’s see… readers might be surprised to learn:

To unwind or relax, I get really caught up in watching True Crime stories and contemplating what makes people do the things they do. (Admittedly, sometimes the crimes are so grisly and the criminals so fascinating and repugnant, it defeats the “unwind or relax” aspect of the viewing!)

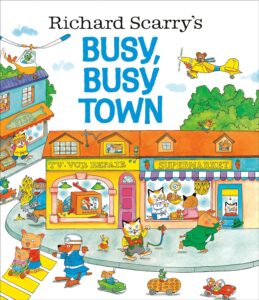

I got my start in the children’s publishing business assisting Olé Risom, the Random House editor who edited Richard Scarry and Laurent de Brunhoff, so I had the pleasure of working with both. I grew up reading Scarry’s Busytown series and de Brunhoff’s Babar series, so to work and get to know these masters was an utterly delightful and serendipitous experience for which I’m so grateful.

I got my start in the children’s publishing business assisting Olé Risom, the Random House editor who edited Richard Scarry and Laurent de Brunhoff, so I had the pleasure of working with both. I grew up reading Scarry’s Busytown series and de Brunhoff’s Babar series, so to work and get to know these masters was an utterly delightful and serendipitous experience for which I’m so grateful.

I’m not afraid to speak in public, I’m not afraid to try new foods, I’m not afraid to travel by myself. I am, however, afraid of steep hills (going down or going up!)—much to the frustration of family and friends with whom I am supposed to be having fun skiing or hiking!

DO: Thanks so much, Emma!

This month’s Industry Insider interview is with Deidra Purvis, an Acquisitions Editor for Free Spirit Publishing, an imprint of Teacher Created Materials. Free Spirit is the “leading publisher of social and emotional learning books for kids, teens, and educators.” The press also notes that it’s “unabashedly pro-kid.” Love that, right?

This month’s Industry Insider interview is with Deidra Purvis, an Acquisitions Editor for Free Spirit Publishing, an imprint of Teacher Created Materials. Free Spirit is the “leading publisher of social and emotional learning books for kids, teens, and educators.” The press also notes that it’s “unabashedly pro-kid.” Love that, right?

engaging, lyrically written, and include elements of fun and humor–and they cover a broad range of issues important to kids—from celebration of identity and family to tough topics like anxiety and grief. A good example of a Free Spirit book is

engaging, lyrically written, and include elements of fun and humor–and they cover a broad range of issues important to kids—from celebration of identity and family to tough topics like anxiety and grief. A good example of a Free Spirit book is

I do not agree with you “that there are some elements good stories need, like conflict and tension, that keeps the story moving and the reader reading.” I see this all the time in craft books and I disagree. Many cultures do not tell stories this way. Yet, they tell amazingly good stories. We cannot dismiss stories because it doesn’t follow the standards of whiteness. We have to respect cultures and embrace those cultures and their style of storytelling. This is why we are at the point in publishing where there’s a need and cry for “diverse books and stories.” Authentic storytelling is not one way, it isn’t a cookie-cutter narrative. Authentic storytelling is how that culture tells stories and what stories they deem necessary to be told. And I would hope that others would want to experience how different cultures document their stories.

I do not agree with you “that there are some elements good stories need, like conflict and tension, that keeps the story moving and the reader reading.” I see this all the time in craft books and I disagree. Many cultures do not tell stories this way. Yet, they tell amazingly good stories. We cannot dismiss stories because it doesn’t follow the standards of whiteness. We have to respect cultures and embrace those cultures and their style of storytelling. This is why we are at the point in publishing where there’s a need and cry for “diverse books and stories.” Authentic storytelling is not one way, it isn’t a cookie-cutter narrative. Authentic storytelling is how that culture tells stories and what stories they deem necessary to be told. And I would hope that others would want to experience how different cultures document their stories. The takeaway message to self-published authors is to spend a lot of time and thought putting your book together. The Churchmans [a couple who self-published] looked at formats and chose the largest trim size that could fit comfortably on standard shelves. They printed the book on 100lb paper—heavier stock than most traditional publishers can use—and also used extra heavy board for the hardcover case. They hired an editor to help them shape the text. And they mounted a Kickstarter campaign to fund their upfront costs. They took a lot of care.

The takeaway message to self-published authors is to spend a lot of time and thought putting your book together. The Churchmans [a couple who self-published] looked at formats and chose the largest trim size that could fit comfortably on standard shelves. They printed the book on 100lb paper—heavier stock than most traditional publishers can use—and also used extra heavy board for the hardcover case. They hired an editor to help them shape the text. And they mounted a Kickstarter campaign to fund their upfront costs. They took a lot of care. I’m most likely to pass on rhyming picture books or picture books that cover ground that’s well-trod (alphabet books, goodnight books). That’s both personal taste and a business decision. For example, it’s extremely hard to pull off rhyme. And in a market flooded with “goodnight” books, it can be hard to make another one stand out in the crowd. Also, just as a matter of personal taste, I don’t like treacly-sweet “I love you” books.

I’m most likely to pass on rhyming picture books or picture books that cover ground that’s well-trod (alphabet books, goodnight books). That’s both personal taste and a business decision. For example, it’s extremely hard to pull off rhyme. And in a market flooded with “goodnight” books, it can be hard to make another one stand out in the crowd. Also, just as a matter of personal taste, I don’t like treacly-sweet “I love you” books. First, when I started in children’s publishing, we were just beginning to see books like Harry Potter,

First, when I started in children’s publishing, we were just beginning to see books like Harry Potter,  People in children’s book publishing are often drawn to this industry, at least in part, because it offers a chance to do something meaningful and positive in the world. I think it’s safe to say that with the start of the Trump administration, many acquiring editors feel uniquely positioned to help counter some of the policies or currents of opinion—about immigrants, about diversity, about

People in children’s book publishing are often drawn to this industry, at least in part, because it offers a chance to do something meaningful and positive in the world. I think it’s safe to say that with the start of the Trump administration, many acquiring editors feel uniquely positioned to help counter some of the policies or currents of opinion—about immigrants, about diversity, about

I can tell from the first page if I want to read on. I tag as I look through things: yes, no, further investigation needed. I am looking for specific stories now and specific writing qualities. If it is something I might be interested in, I give it three chapters. I need to be compelled in three chapters or I pass. After that, if I am still interested, I request. Once a full manuscript comes in, I read it with an eye for how much work it will need, and if I have a vision or feel compelled. I have perfectly lovely manuscripts that I pass on because I just didn’t find that passion. And passion drives the ship. When you are neck deep in 13 passes from editors, you want to feel that spark of joy that makes you say, “Screw this, I know I am right.”

I can tell from the first page if I want to read on. I tag as I look through things: yes, no, further investigation needed. I am looking for specific stories now and specific writing qualities. If it is something I might be interested in, I give it three chapters. I need to be compelled in three chapters or I pass. After that, if I am still interested, I request. Once a full manuscript comes in, I read it with an eye for how much work it will need, and if I have a vision or feel compelled. I have perfectly lovely manuscripts that I pass on because I just didn’t find that passion. And passion drives the ship. When you are neck deep in 13 passes from editors, you want to feel that spark of joy that makes you say, “Screw this, I know I am right.” I think as writers we often forget how many plates agents have to spin and that most agents still need a day job to survive financially. Being on the other side of things helped me understand timing and what goes into deciding what projects to represent. While there are so many wonderful stories out there that I may fall in love with, there’s also an element of how I can make this book great and if I can sell it. Oftentimes, as writers we idolize the idea of getting an agent and forget that it is a business partnership as well. The reason why it takes so long for agents to get back to writers right away is because clients come first and it takes time to read, to make sure the project will be the right partnership. That being said, I wish I knew how much went into agenting before I started querying because now a rejection isn’t something I worry about and I understand if it takes long, it actually might be a good thing. It’s all about patience, right timing and working on your craft in the meantime.

I think as writers we often forget how many plates agents have to spin and that most agents still need a day job to survive financially. Being on the other side of things helped me understand timing and what goes into deciding what projects to represent. While there are so many wonderful stories out there that I may fall in love with, there’s also an element of how I can make this book great and if I can sell it. Oftentimes, as writers we idolize the idea of getting an agent and forget that it is a business partnership as well. The reason why it takes so long for agents to get back to writers right away is because clients come first and it takes time to read, to make sure the project will be the right partnership. That being said, I wish I knew how much went into agenting before I started querying because now a rejection isn’t something I worry about and I understand if it takes long, it actually might be a good thing. It’s all about patience, right timing and working on your craft in the meantime. A big part of this process for me is trying to make sure that the surface story and takeaway are strong enough to catch an editor’s attention and enable them to see the bigger picture. I’m not an editor in the way that your editor, Frances Gilbert, is and she will definitely make

A big part of this process for me is trying to make sure that the surface story and takeaway are strong enough to catch an editor’s attention and enable them to see the bigger picture. I’m not an editor in the way that your editor, Frances Gilbert, is and she will definitely make

I always ask myself whether this is something children actually

I always ask myself whether this is something children actually  I’m open [to self-published or indie authors] so long as the project they’re querying hasn’t already been published. Those I won’t take on because the project really needs to be an Indie bestseller in order for editors to consider it. Otherwise it doesn’t really matter to me unless those projects are problematic/poorly written. My general advice is don’t try to use self-publishing as a way to launch yourself into traditional publishing. It backfires more often than it works.

I’m open [to self-published or indie authors] so long as the project they’re querying hasn’t already been published. Those I won’t take on because the project really needs to be an Indie bestseller in order for editors to consider it. Otherwise it doesn’t really matter to me unless those projects are problematic/poorly written. My general advice is don’t try to use self-publishing as a way to launch yourself into traditional publishing. It backfires more often than it works. If I’m intrigued, I send insights about areas to revise. I don’t want to hear back in, like, two hours because I don’t believe the writer will have really pondered and had opportunity to decide whether the revisions seem like a direction that feels right. But I also want to hear back in some reasonable amount of time (a few months would be really long for a picture book, unless my thoughts for revision would have major impact on illustrations for an author/illustrator).

If I’m intrigued, I send insights about areas to revise. I don’t want to hear back in, like, two hours because I don’t believe the writer will have really pondered and had opportunity to decide whether the revisions seem like a direction that feels right. But I also want to hear back in some reasonable amount of time (a few months would be really long for a picture book, unless my thoughts for revision would have major impact on illustrations for an author/illustrator). I particularly love what I call “historical footnote” picture books, that build a story around lesser known bits from history. I’m also looking for picture books that capture ordinary or natural moments that feel like they’re magical—moments like capturing fireflies, bread dough rising, watching a bird murmuration, the Northern Lights, planting a seed and having it grow into a living plant, and so on. We’re surrounded by ordinary magic, and I want to celebrate it! I’m also particularly looking for picture books that explore something peculiar that happens in nature.

I particularly love what I call “historical footnote” picture books, that build a story around lesser known bits from history. I’m also looking for picture books that capture ordinary or natural moments that feel like they’re magical—moments like capturing fireflies, bread dough rising, watching a bird murmuration, the Northern Lights, planting a seed and having it grow into a living plant, and so on. We’re surrounded by ordinary magic, and I want to celebrate it! I’m also particularly looking for picture books that explore something peculiar that happens in nature. One interesting thing is that independent booksellers have been compelled to be so much more nimble and creative to stay competitive and so many of them have gotten really good at selling picture books and middle-grade books.

One interesting thing is that independent booksellers have been compelled to be so much more nimble and creative to stay competitive and so many of them have gotten really good at selling picture books and middle-grade books. I regularly see picture book biography texts that are well done but just don’t completely grab me. A common problem with these is pacing. Everything in the subject’s life is given equal weight, so the highs don’t feel all that high nor do the lows feel all that low.

I regularly see picture book biography texts that are well done but just don’t completely grab me. A common problem with these is pacing. Everything in the subject’s life is given equal weight, so the highs don’t feel all that high nor do the lows feel all that low. Communication is key!!! It’s so important to me that my clients feel comfortable talking to me about any concerns they have throughout the process. I am always here! Most authors will feel a range of emotions throughout the submission process and beyond. Are you feeling disheartened? Would you like to talk strategy? Do you have editors you’d like me to submit to? Are you confused about contract language or what something means? I am always open to suggestions as well. It’s a partnership! Every author is different as far as how often they want to communicate and in what way (phone, email, etc.) and how involved they want to be in particular aspects of the process. So, I always like to be as clear on those details as possible. I want everyone I work with to be happy, know that I have their back, and be comfortable talking through things with me.

Communication is key!!! It’s so important to me that my clients feel comfortable talking to me about any concerns they have throughout the process. I am always here! Most authors will feel a range of emotions throughout the submission process and beyond. Are you feeling disheartened? Would you like to talk strategy? Do you have editors you’d like me to submit to? Are you confused about contract language or what something means? I am always open to suggestions as well. It’s a partnership! Every author is different as far as how often they want to communicate and in what way (phone, email, etc.) and how involved they want to be in particular aspects of the process. So, I always like to be as clear on those details as possible. I want everyone I work with to be happy, know that I have their back, and be comfortable talking through things with me. A picture book is more than anything else a piece of theater, with pictures and words unfolding together as the pages turn and turn and turn all the way to that most important and satisfying one—the final turn from pages 30–31 to page 32.

A picture book is more than anything else a piece of theater, with pictures and words unfolding together as the pages turn and turn and turn all the way to that most important and satisfying one—the final turn from pages 30–31 to page 32. Three hundred and fifty words is definitely on the short end of the picture books we publish! Word counts can vary greatly depending on things like the age group they’re targeting, and whether they’re fiction or nonfiction.

Three hundred and fifty words is definitely on the short end of the picture books we publish! Word counts can vary greatly depending on things like the age group they’re targeting, and whether they’re fiction or nonfiction. In terms of process, it’s [writing a picture book] sort of a cross between composing a poem and writing a short essay. For many years I did a column for

In terms of process, it’s [writing a picture book] sort of a cross between composing a poem and writing a short essay. For many years I did a column for  If I knew the formula for making a finished book irresistible, I would be a millionaire. Even after years of experience, I find it hard to anticipate which titles will really take off. I always pause when I have the first bound book in my hands and celebrate that achievement. What the market thinks is out of our control. Nevertheless, most bookstores use the top seasonal holidays as a hook for a display. Back to school is another important season for picture books. It goes without saying, that the publisher has priced the book competitively and the trim size is right for the story, i.e. some books are “lap books” that can be spread across the laps of two readers; some illustrations call for vertical size and others for landscape.

If I knew the formula for making a finished book irresistible, I would be a millionaire. Even after years of experience, I find it hard to anticipate which titles will really take off. I always pause when I have the first bound book in my hands and celebrate that achievement. What the market thinks is out of our control. Nevertheless, most bookstores use the top seasonal holidays as a hook for a display. Back to school is another important season for picture books. It goes without saying, that the publisher has priced the book competitively and the trim size is right for the story, i.e. some books are “lap books” that can be spread across the laps of two readers; some illustrations call for vertical size and others for landscape. So what does it mean to have a book for kids aged 3–7? It means that you need to focus on things these children can understand and can relate to. Keep in mind what a young kids’ experience with the world is and what is interesting to them. A four-year-old isn’t going to want to read a book about a ten-year-old. They can’t relate to what that character is going through and probably won’t understand the book. Young children are still learning how the world works and wont usually comprehend more complex emotional stories. That’s why most picture books tend to be simplified. A book about bullying, for example, would likely focus on a protagonist stepping up to stop the bullying, not the actual physical and emotional abuse the bullied child experiences.

So what does it mean to have a book for kids aged 3–7? It means that you need to focus on things these children can understand and can relate to. Keep in mind what a young kids’ experience with the world is and what is interesting to them. A four-year-old isn’t going to want to read a book about a ten-year-old. They can’t relate to what that character is going through and probably won’t understand the book. Young children are still learning how the world works and wont usually comprehend more complex emotional stories. That’s why most picture books tend to be simplified. A book about bullying, for example, would likely focus on a protagonist stepping up to stop the bullying, not the actual physical and emotional abuse the bullied child experiences. Welcome to this month’s Industry Insider guest, Taylor Norman, a rock star in the realm of children’s literature as Executive Editor at Neal Porter Books/Holiday House. Let’s give her a big, warm welcome!

Welcome to this month’s Industry Insider guest, Taylor Norman, a rock star in the realm of children’s literature as Executive Editor at Neal Porter Books/Holiday House. Let’s give her a big, warm welcome!

Welcome to Meredith Mundy, the Editorial Director at Abrams Appleseed. With a career spanning over two decades, Meredith’s keen eye for quality has helped discover and nurture many talented authors and illustrators. Her work on everything from an

Welcome to Meredith Mundy, the Editorial Director at Abrams Appleseed. With a career spanning over two decades, Meredith’s keen eye for quality has helped discover and nurture many talented authors and illustrators. Her work on everything from an