June’s Author Interview is with English zoologist and writer Nicola Davies, who was one of the original presenters for the terrific BBC children’s show “The Really Wild Show.” Nicola got her first pair of binoculars at age eight, and she’s been gazing out at the world of animals ever since, from geese in Scotland to humpbacked whales in NewFoundland to chameleons in Madagascar to bat-eared foxes in Kenya to saltwater crocodiles in Australia.

June’s Author Interview is with English zoologist and writer Nicola Davies, who was one of the original presenters for the terrific BBC children’s show “The Really Wild Show.” Nicola got her first pair of binoculars at age eight, and she’s been gazing out at the world of animals ever since, from geese in Scotland to humpbacked whales in NewFoundland to chameleons in Madagascar to bat-eared foxes in Kenya to saltwater crocodiles in Australia.

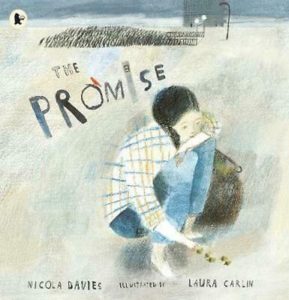

Oh, and she’s written a good number of things along the way, including novels, poetry, and picture books. A few OPB favorites include:

That’s it–thinking about those books again has me excited to hear from Nicola. Let’s get right to the interview!

RVC: Which came first—the love for animals or the love for stories?

ND: I don’t think I could separate them. I came from a family which loved both. My father trained as a biologist and was a keen naturalist but he loved poems and stories too, so information was always imparted in some kind of narrative. My mother was a natural storyteller and instinctively packaged information in narrative. So I grew up with nature poetry and story twined together.

RVC: What inspired you to combine your love of stories with the love of animals?

ND: Entirely intuitively. The natural world is full of ready-made stories…seasonal cycles, life cycles, nutrient cycles, food chains–all of these are narratives ready and waiting to be retold.

RVC: On a scale of 1 to 10, how interested are kids in animals?

ND: Oh, about 12! I’ve never met a child who wasn’t instinctively connected with and interested in nature. That is the connection that I seek to deepen and strengthen into a lifetime bond.

RVC: Most of your kidlit seems to blend nonfiction and fiction. How do you find the balance?

ND: Narrative is a psychological carrier bag–it can carry real facts and invented ones. But with an invented narrative structure that carries real facts, the narrative itself also has to reflect reality and the factual content you want to deliver. With my hero of the wild series, real conservation stories are told through the medium of invented characters and storylines, but both character and plot are very closely based on real people and events.

ND: Narrative is a psychological carrier bag–it can carry real facts and invented ones. But with an invented narrative structure that carries real facts, the narrative itself also has to reflect reality and the factual content you want to deliver. With my hero of the wild series, real conservation stories are told through the medium of invented characters and storylines, but both character and plot are very closely based on real people and events.

The Lion Who Stole My Arm is based on a real conservation project in Mozambique, in the Niassa reserve, and the child at the centre of the story on a real child who was attacked by a lion. The only things I changed were the location of the child to just over the border in Tanzania; the age of my character is 10, the real one 5; and which arm he lost, with the real child losing the left and my character the right. Then I engineered the plot to reveal other background aspects of the real situation. It’s like patchwork!

I did the same with Ride the Wind–a story about a Chilean fisher family who catch an albatross on their long line. It conveys information about the catching of endangered sea birds but also about how some S and C American families are affected by migration to the US. Ditto my book about Hummingbirds.

RVC: Ideally, where do you want those books shelved in the library or at a bookstore?

ND: Anywhere where kids will find them! Ideally two copies–one in fiction and one in nonfiction.

RVC: You’re the first person I’ve interviewed here who worked with/for the BBC. How did you get that gig, and what was it like?

ND: I was working on a PhD on bat feeding ecology at Bristol University, just a five-minute walk from the NHU’s home at the BBC in Bristol. When it became obvious that the Tory government were cutting grants for primary research and that, in any case, research would be “preaching to the choir,” I jumped ship and knocked on their door until they let me in. But I wasn’t really cut out for TV–it was very competitive and I’m not good at competing.

I did discover that I could write, so I started writing scripts for the programmes I presented.

RVC: You’ve said before that “while every book is a story, every book also has its own story of how it came to be.” What’s the story behind Gaia Warriors, which is a book about climate change?

RVC: You’ve said before that “while every book is a story, every book also has its own story of how it came to be.” What’s the story behind Gaia Warriors, which is a book about climate change?

ND: My publisher was approached by James Lovelock who wanted to collaborate with a children’s writer to do a book about climate change. I was reluctant to work with him but I was persuaded, and in the end he just left me to it and we got on fine.

I wanted to do a book that gave children:

- the arguments to use to put forward the case to climate change deniers,

- hope that action is possible,

- examples of interesting ways to live their lives that would be stimulating, satisfying, AND fight CC.

RVC: What’s the most important thing writers should know or understand about creating a picture book that deals with a tough topic?

ND: Do your research. Talk to people who have experienced what you write about even if you also have your own experiences to draw on. Be sensitive, be brave, and remember there are as many ways to tell the same story as there are threads in a spider’s web. Find your way.

RVC: Your book Ju st Ducks! came out just a few months back. How do you go about writing a book like that so it’s more than just a pile of duck facts?

st Ducks! came out just a few months back. How do you go about writing a book like that so it’s more than just a pile of duck facts?

ND: Find the true narrative that carries the facts. In this case it was easy…I really did live in a house by the river (the river Exe in Devon ) and I heard ducks every morning. So everything in that book happened to me multiple times. All I had to do was imagine it happening to a young child.

RVC: You’ve got a very strong view on what narrative is. Care to share it once again?

ND: It’s a piece of writing with a shape. A beginning, a middle, and an end. It should be memorable–i.e. psychologically portable. It should have a clear voice that speaks to the reader. And I like narratives with answered questions and open ends that the reader can think about and engage with.

RVC: I’m guessing that the reason you sometimes rhyme—as you do in The Secret of the Egg and other books—stems from your love of poetry. What are some strategies for getting rhyme to really work in a picture book?

RVC: I’m guessing that the reason you sometimes rhyme—as you do in The Secret of the Egg and other books—stems from your love of poetry. What are some strategies for getting rhyme to really work in a picture book?

ND: Well, the first is to have an editor who lets you do it. Not all allow it.

The second is don’t let the rhyme dictate the thought. Don’t use words you’d never otherwise use just to rhyme (unless you can make a really good aural joke with it). Be super careful with meter…don’t cheat!

RVC: One last question for this part of the interview. In all your experience in writing children’s literature, what has surprised you the most?

ND: I’ve had many lovely surprises from children who respond to and remember bits of my books, identify with characters, and point out things I’ve never thought of. It’s the BEST part of writing for kids.

RVC: Alright. Here we go with the Speed Round! Six fast questions coming at you, starting with…most underappreciated animal?

ND: All the ones that we allow to go extinct before we even named them. All the unseen insects and soil invertebrates that hold ecosystems together, on whom our very lives depend and which we totally ignore. Darwin understood this. That’s why he spent so much time studying earthworms.

RVC: Most underappreciated Welsh food?

ND: Lava bread. It looks a bit like fresh cow poo but is wonderful and very good for you. (It’s seaweed!)

RVC: Which animal would you most want to write a picture book biography about you?

ND:The tiger in my new novel The Song That Sings Us. He’s called Skrimsli.

RVC: Your favorite animal picture book of 2020?

ND: The Lost Spells by Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris.

RVC: Your one-sentence mission as a picture book auth or?

or?

ND: To fan the spark of childhood curiosity into a lifelong bonfire.

RVC: Best compliment a child reader ever gave you?

ND: About my book The Promise, a very disadvantaged child from a school in Boston said, “THAT BOOK WAS ABOUT ME!”

RVC: Thanks so much, Nicola! This was terrific.